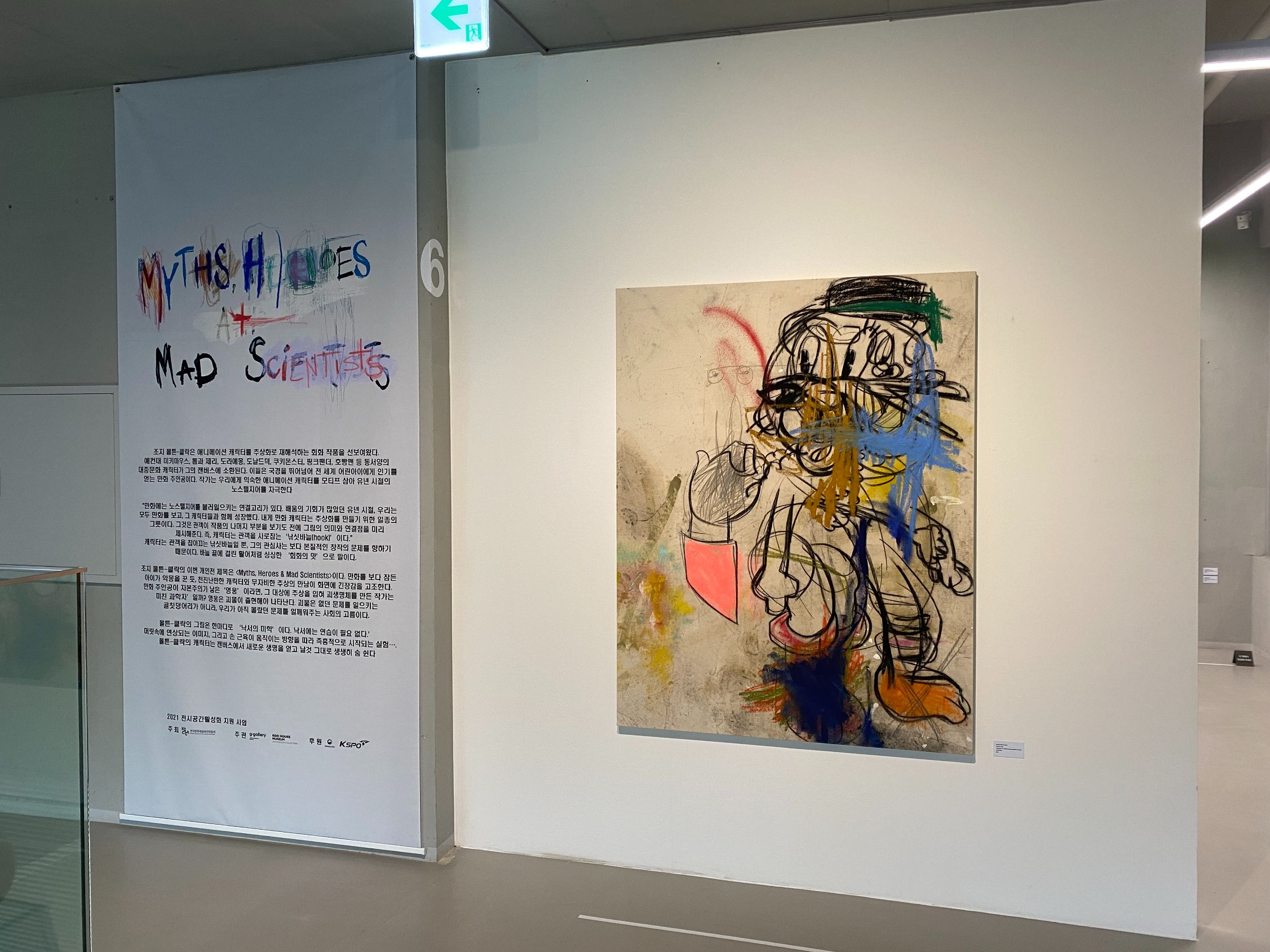

Solo Show, Koo House Museum, South Korea

Myths, Heroes and Mad Scientists

The Favoured Refugees

Myths, Heroes and Mad Scientists

/ Hyun YI (Deputy Editor-in-Chief of Art In Culture)

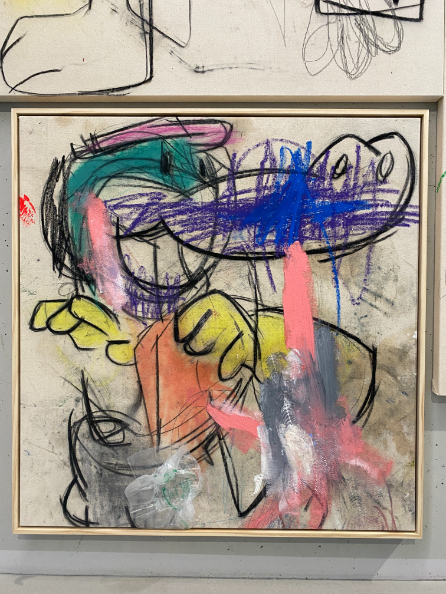

George Morton-Clark is a British artist. His work resembles scribbles on a child’s sketchbook at first glance, with intense monochromatic colors, flat compositions without perspective, scenes full of atypical lines rushing like a storm. Morton-Clark’s artistic world is rooted in cartoon characters that pop up unexpectedly from the chaos. It is still unknown whether the coarse lines surrounding the familiar icons express a rope that suppresses the protagonist or an effect of expressing the moment when a hero is born in a place like a magic lamp.

The artist clearly defined the characters appearing in his paintings. “There is a very nostalgic connection to cartoons. We all see and grow up with them in our most informative years. I use these images as a vessel to create abstractions in my work. It gives the viewer already a meaning and a connection to the painting before they look at the rest of the picture. This is a hook to capture the viewer.”

Morton-Clark uses characters from the pop culture of the East and West, such as Tom and Jerry, Doraemon, Donald Duck, Cookie Monster, Pink Panther, and Anpanman, as the ‘vessel of shapes.’ However, the way they are expressed is more like a ‘broken container.’ Reflecting on the artist’s words, we can see that the characters are just like a hook to capture the viewers. The artist’s interest is directed toward more fundamental issues of creation. It is done with a ‘taste of painting’ that is as alive as a live fish caught on the tip of a hook. The artist majored in animation at university, but he swiftly turned to painting. The decision shows his intention to enjoy the beauty of painting in abundance. “With animation, I did not have as much creative control as I wanted. After studying for 3 years I realised even though I loved it, it was not for me. I love the freedom and the mess you can make with brushes and canvas. The immediacy of using paint on a canvas and seeing it in real life, this you will not find in animation.”

However, examining Morton-Clark’s paintings in time, one can see that the message is by no means simple. The artist does not stop at staying in the world within the canvas, indulging the materiality of artistic materials. He also maintains a sharp perspective that penetrates the reality outside the canvas. While his initial thematic concern was ‘what kind of painting to pursue,’ his next concern is ‘what to express with painting.’ While he destabilized the refined frame of animation to advance toward abstraction in the former, he engages an outlook of the 21st-century dystopia through cartoon characters once again.

As the artist said, we all watched cartoons when we were young and grew up with the

characters. It is no exaggeration to say that well-known cartoon characters that transcend

nationalities are the common denominator of humankind in contemporary time. Even at this moment, more and more characters are being created. Multinational animation companies are accumulating enormous wealth. We grew up watching animations, and our next generations will also embrace similar content through televisions, smartphones, and screens. Yet, we really have no choice other than this. There is no ground left for our children to play. In the face of skyrocketing land prices and extreme urbanization, animation is a content industry that provides stimulating entertainment in the most efficient way within a small area. Outside the fantasy of the ‘garden of dreams,’ there is a reality of fierce battles over the copyright of cartoon characters.

George-Morton Clark’s solo exhibition is titled Myths, Heroes & Mad Scientists. The

encounter between innocent cartoon characters and ruthless abstraction, which reminds of a nightmare of a child who fell asleep watching a cartoon, heightens tension on the canvas. If the cartoon characters are the ‘heroes’ produced by capitalism, is the artist who created the monsters by abstracting them a ‘mad scientist’? Heroes emerge only when monsters appear. Monsters are not a nuisance causing problems that did not exist before them. Rather, they are purulent matters that remind us of the problems we have not been aware of.

In a word, Morton-Clark’s paintings show the ‘aesthetics of scribbling.’ Scribbling does not require practice. It is an impromptu experiment that begins with images that come to one’s mind, following the direction of muscles in one’s hands. Morton-Clark’s characters come to life on the canvas and breathe with rawness and vitality. His paintings are ‘Frankensteinish’ monsters that both stimulate the nostalgia of their viewers and reflect the dark side of society at the same time.

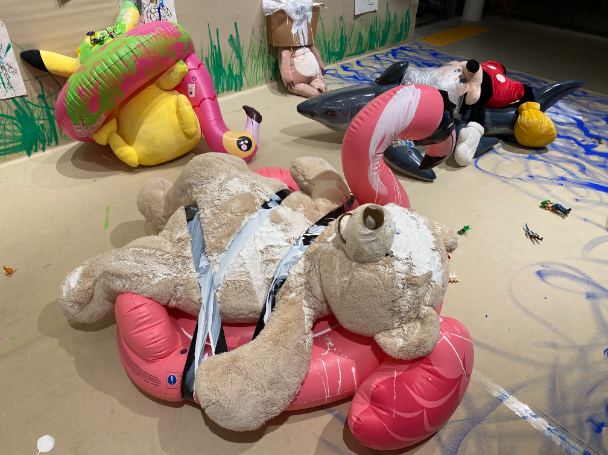

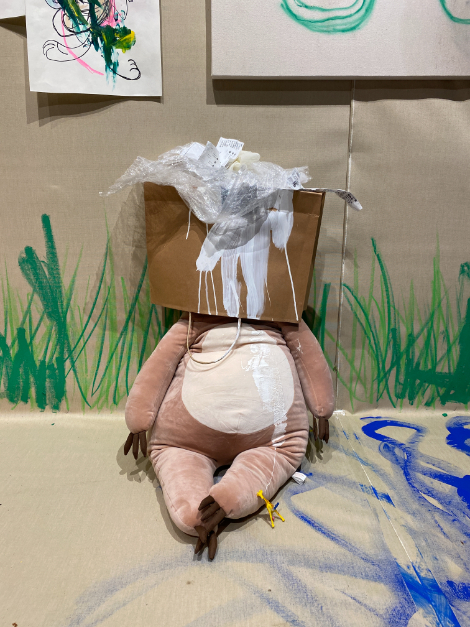

The Favoured Refugees

Objects seemingly straight out of one of George Morton-Clark’s paintings are placed on the beach; as if swept there by the waves. The objects, named “The Favoured Refugees”, are a comment on the migrant crisis facing many countries. In Dover, England, refugees travel from France looking for safety and a new life. They arrive on dinghies or makeshift boats. Many will leap into the water because maritime law dictates that anyone in distress at sea must be saved. Once a refugee is pulled onto a British boat they become the responsibility of the United Kingdom. Some policy-makers in England want to change the law so that immigrants are sent directly back to France. In a world where people are driven by desperation to risk their lives and the lives of their families in the hope of a better life, we should favour the refugee; look at who they really are and what they bring, not view them as the enemy.