It’s Friday All Week

Opera Gallery Madrid is pleased to present “It’s Friday All Week”, the first solo show in Spain by the British artist George Morton-Clark, showcasing his most recent work.

Bringing George Morton-Clark’s work to Opera Gallery reflects a desire to convey our in-built philosophy of vital optimism—through the vibrant empathy his works arouse in the beholder. The animated cartoon characters in his paintings radiate a hunger for life. They transport us to a high-spirited world where fun and laughter burst and free us of our everyday routine, infecting us with their liveliness and spontaneity. It is no surprise that whenever we stop in front of any of his works, our mind begins spinning a tale that takes us out of the present moment and immerses us into an exhilarating scene of motion and action. We are even further enmeshed in their web by the titles he gives his works, which hook us straight into the action.

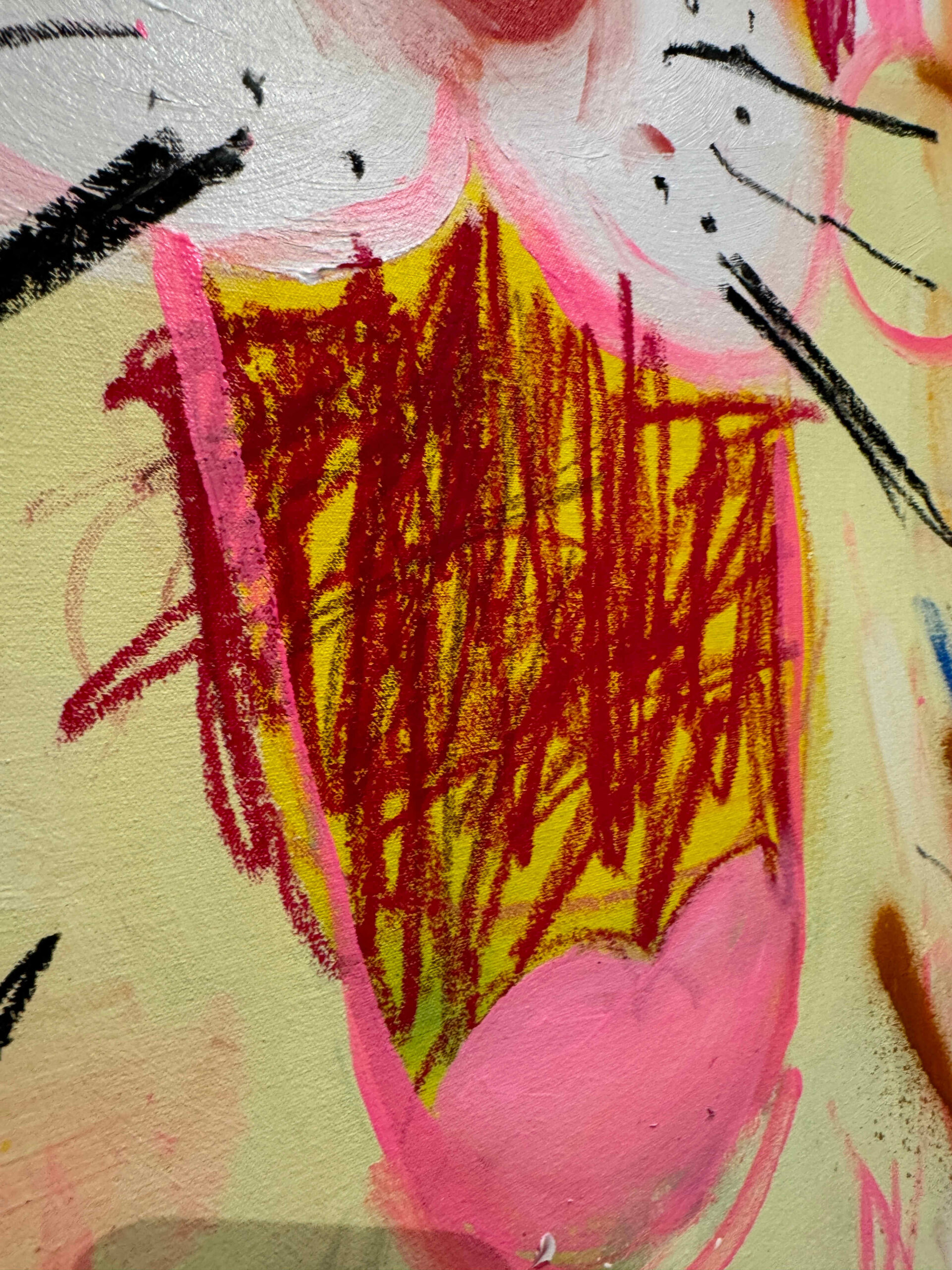

The painter describes his menagerie of characters as follows: “All paintings are an amalgamation of images in my head and characters I spent a long time with them. They come out in different forms and different expressions. All of the time, I feel I am trying to make them more vacant-looking and void of any real emotion. I am not sure why I do this, but it makes them more innocent and friendly. This is what I like about them. The newer works have become more abstract, as if the characters are imploding and eating themselves. As if they are infinitely folding into themselves”.

This first solo show by Morton-Clark in Spain tallies to perfection with the core foundation on which Opera Gallery builds its philosophy of Thinking Global–Acting Local. A crucial paradigm to appreciate our approach to Art and the edifying and transformative role it plays in our society as part of the cultural fabric of the cities where our galleries are located, supporting and promoting the work of our artists internationally. And so, each one of Morton-Clark’s brushstrokes not only submerges us in his world but also encourages us to actively partake in a global cultural dialogue grounded in the very essence of our local communities.

GEORGE MORTON– CLARK

IN CAT ALLEY

By Pedro Medina Reinón

Immortalised by Ramón María del Valle-Inclán, and one of the city’s legendary streets, Cat Alley is the place from where Max Estrella set out on his wanderings through Madrid. In Bohemian Lights Valle-Inclán describes the concave mirrors in the street that distorted the world and reflected the grotesque face of reality. The result of this approach is that we can engage with our environment in a lateral and emotional way rather than through a frontal description.

That being said, and as happens with so many literary worlds, we may well have idealised this image. Though we still have mirrors to- day, the reflections we can create of ourselves are much more limited, on a surface that is not the original and in a setting that has lost the pedigree of those erstwhile times. In front of new mirrors, we can still ask ourselves who we are, what perception others have of us and we have of ourselves; in other words, although the literary myth is still able to gain adepts, it should come as no surprise that the beholder is also stricken by a certain sense of melancholia.

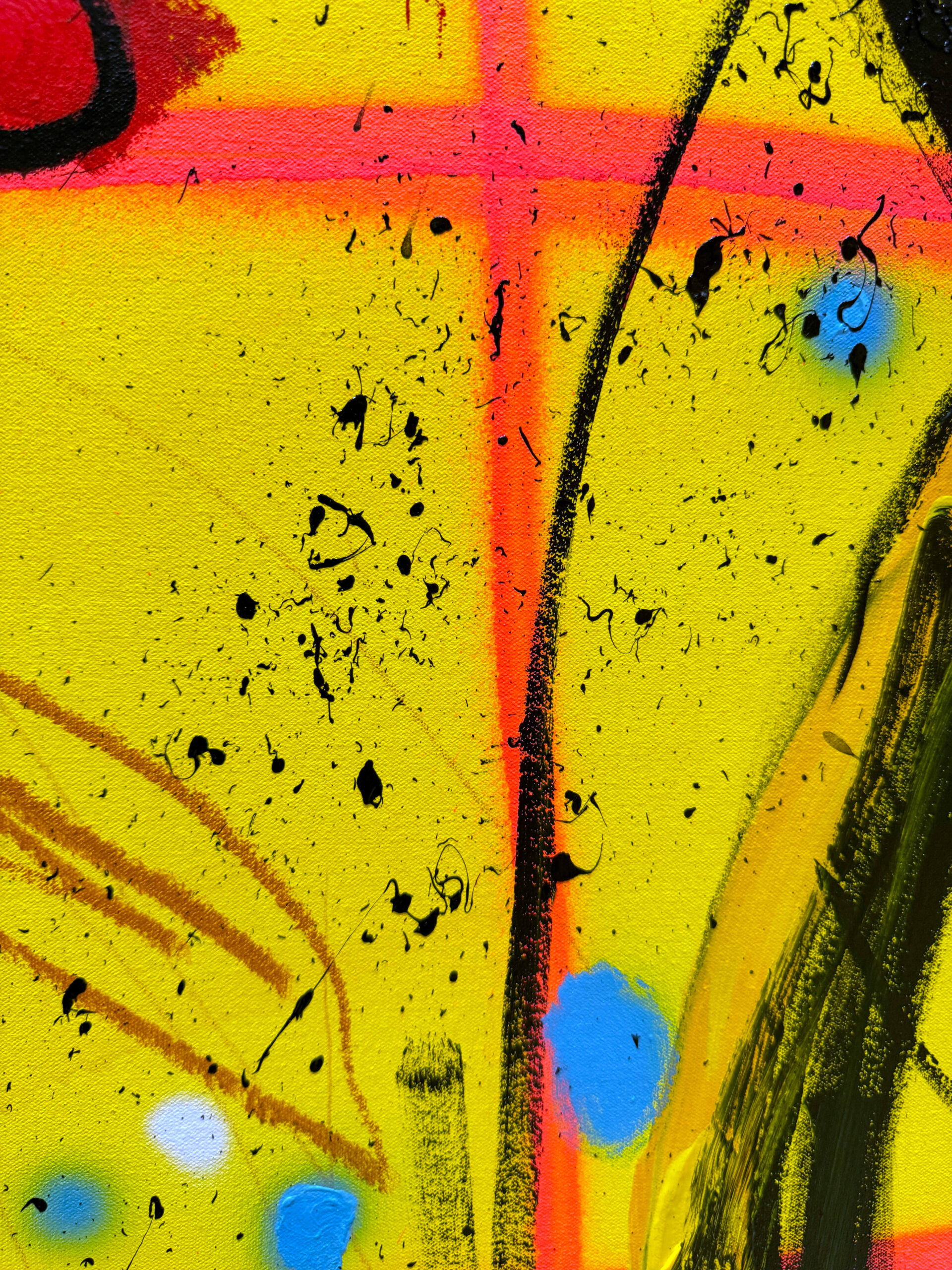

Speaking with George Morton-Clark about his work is like being guided by both Max Estrella and Don Latino, injecting life into hearty zeal and yearning intimacy, a quick-witted sense of humour and depths of memory. Indeed, when we first glance at the British artist’s canvases, we are generally greeted by a familiar imaginary of cartoons, he appropriated with spirited resourcefulness and underscored with marked monumentality and chromatic vividness. He intervenes on it with assertive brushwork, driven by a gesture that instils an exhilaratingly intense rhythm.

Many disparate experiences converge in this style. Firstly, we have the years he spent studying animation in the UK. Yet, despite the evident influence left on his visual work, the world he depicts is very varied and can be traced much further back, to his childhood. Therein the variety of sources and also the nostalgic tinge, because that time is long gone, though perhaps only to eternally return, like the mirror in Cat Alley.

With his ability to reinterpret cartoon characters from his childhood, Morton-Clark invites us on an introspective journey that couples the familiar and the abstract to create a unique visual dialogue. In addition, one ought to point out that this focus not only denotes a stylistic choice, but is in fact the medium to explore our emotional relationship with these characters. By rendering them in canvas paintings, the artist divests these icons of their childlike innocence and submerges us into a new narrative in which nostalgia is inflected with the complexity of the adult experience.

In doing so, Morton-Clark forces us to question the images that shape our imaginary and our relationship with it, because as Marshall McLuhan or John Berger might say, “we are what we see.” We are constantly surrounded by images, immersed in a reality that has been filtered through television, the medium that revolutionised messages and decisively influenced a collective imaginary that is no longer li- terary nor classical, but pure presentness, that speaks not so much of gods but, if anything, of characters like Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck or the Pink Panther, in order to crack a smile on the face of adults who recognise the source and to appreciate the novel quality the image accrues in this context.

In such an international gallery like Opera Gallery, the artistic appropriation in “It’s Friday All Week” becomes a powerful instrument to explore the influence of popular culture in our collective psyche, activated by iconic cartoon characters with the purpose of conjuring shared memories. In this way, he manages to kindle an experience that functions not only in Western settings, but has shown itself to be universal, as borne out in his recent shows in Singapore and South Korea. Accordingly, Morton-Clark’s work is underpinned by the lucidity Gillo Dorfles discerned in his exhibition in Madrid in 2016: it is necessary to speak in favour of the version, because we need to envisage “more expressive and interpretative possibilities regarding the reinter- pretation the version makes of the original; yet another face for a new metamorphosis.”

And then a certain destabilising irony comes into play, the offspring of nostalgia, humour and the newfound energy patent in these drawings, unquestionably reminiscent of Pop Art. However, in Morton- Clark this is all executed in robust, chaotic and even violent brushwork.

At the same time, it is underpinned by technical prowess capable of deftly balancing visceral expressiveness with controlled precision, creating masterful harmonic compositions despite accommodating chaos in their interior.

Having said that, one would have to specify that this stylistic deci- sion is not geared towards a critical or political evolution of the work, rather the strength serves to underscore the fact that his relationship with the past has transmuted. He distorts the remembered world while he imbues his canvases with great intensity, thanks precisely to a game of opposites that exemplifies the tension existing between the perspectives of the child and the adult.

To a certain extent, it would also represent the pulse of a “desire”, understood etymologically as de–sidus, literally a “descent of the stars”. In this regard, in their Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue latine, Ernout and Meillet explained the verb “to desire” as redirecting our gaze from the stars towards the Earth, to be able to make our way in the real world, which generated in us a profound nostalgia for something lost. Now Morton-Clark has managed to synthesise a language that situates desire in a particular field of forces and tensions that, in short, asks us to return our gaze upwards to the stars.

From this stance, Morton-Clark’s energetic brushwork helps to ma- nifest these tensions, instilling his work with complexity, ambiguity, dynamism and depth. The bold lines and the saturated colours come to- gether in an extraordinary visual dance, conveying the sensation of im- mediacy and vitality. A vitality one might even define as “Nietzschean”, as it indulges in what is enjoyable and pleasurable in the world, though without ever eschewing its terrible underbelly.

In addition, one can appreciate in his work an abstract gesturality and, at once, an almost expressionist approach to the object. In point of fact, next to his work, one could well imagine listening to the confession that appeared in the correspondence between Kandinsky and Schönberg, when they said that they no longer searched for new experiences in some faraway exotic paradise because they realised that“the true journey of art is inwards”.

In fact, Morton-Clark’s highly personal style was recognised as an extraordinary journey to the interior in Forbes magazine, which called it “doodling aesthetic”. This description is indebted to the immediacy in his work between the mental image and its materialisation, the same immediacy conventionally assigned to drawing, an exceptional medium for quickly giving form to an idea. Indeed, this is how Irina Zucca Alessandrelli, Curator of Collezione Ramo, described it, claiming that it is an intimate practice and “the first form of the idea generated in the artist’s mind.”

Seen in this light, Morton-Clark’s work evinces a sense of freedom in interpreting his thoughts without any interference, demonstrating how art can fuse apparently disparate elements in order to produce a profound reflection. This is the same thing that would happen if we were to contemplate again Max Estrella and Don Latino walking the streets together. Of course, it may not be the bohemian lights of yesteryear, but surely they would gladly surrender to the new slogan “It’s Friday All Week”. Then we would know that, in a grotesque world of esperpento, art can save us and show us new paths of joy and fantasy.